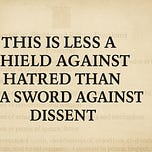

Vague laws don’t silence extremists; they chill everyone else.

The name sounds reassuring: The Combatting Hate Act. Who wouldn’t support a law that promises to protect people from hatred? But laws are rarely about their titles. They are about their clauses, their definitions, and the powers they hand to the state.

Strip away the packaging and Bill C-9 is less about preventing hate crimes than about lowering the charging threshold and expanding government control over speech, protest, and property—especially once Attorney General consent is removed.

What Changed: The End of AG Consent

Until now, prosecutors needed the Attorney General’s approval before laying hate-propaganda charges. That safeguard did three quiet but essential things:

A second look before the state pounces. It forced a sober review in politically heated cases.

National consistency. It helped prevent local, selective prosecutions based on momentary pressure.

Political accountability. A cabinet-level office owned the decision to criminalize speech.

Bill C-9 removes that check. Police and front-line prosecutors can now proceed directly. In real life, that means faster charges, more discretion at the street level, and more opportunities for selective enforcement—with courts acting as the only backstop months or years later.

Key consequence: In protest environments, the process becomes the punishment—arrest, bail conditions, device seizures as “evidence,” public naming and shaming, travel restrictions—all before a judge decides whether the law actually applies.

Where Over-Reach Lives in Bill C-9

1) Symbols — and “look-alikes”

Outlawing Nazi and terrorist symbols sounds straightforward. C-9 goes further: it also bans anything that “resembles” those marks. That vagueness invites case-by-case discretion. A parody, a cartoon, a crossed-out emblem on a placard, or a news photograph can be swept in—then sorted out later at great cost to the accused.

Why AG consent mattered here: it filtered borderline cases where context (journalism, education, art) should prevail. Without it, charges come first, context later.

2) “Hate-crime” overlay for any federal offence

C-9 creates a new offence that escalates penalties if an underlying crime was “motivated by hatred” on listed grounds (race, religion, etc.). Political identity isn’t on that list, but the overlay still raises the stakes in edge cases and gives the Crown leverage at bail and plea.

Why AG consent mattered: it would have screened thin motive theories before they became leverage in negotiations.

3) Restricting protest via “fear” and “access”

New provisions criminalize “fear-provoking” or “interfering” behaviour near religious, cultural, and educational facilities (including daycares and seniors’ residences). Taken literally, loud, proximate, or persistent protest can be painted as intimidation, even if non-violent.

Why AG consent mattered: it reduced the odds that ordinary crowd dynamics get recast as crimes in the heat of the moment.

4) Sweeping forfeiture powers (after conviction)

Courts can seize “anything by means of or in relation to which” an offence was committed. In practice: laptops, cameras, vehicles, organizational funds. Even as a post-conviction remedy, the threat of forfeiture chills independent journalists and organizers and becomes heavy plea-bargain leverage.

Why AG consent mattered: fewer weak speech-based prosecutions reach the point where forfeiture becomes a bargaining chip.

Why This Matters: The Charter and the “Process Penalty”

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms guards expression, assembly, and protection from unreasonable seizure. C-9 pressures all three—not only in court, but before court:

Expression (s.2(b)): “Look-alike” bans and a vague “public-interest” filter for journalism/art chill protected speech.

Assembly & association (s.2(c), s.2(d)): Broad “fear/ access” rules turn robust protest into a legal risk zone around many everyday places.

Seizure (s.8) & fundamental justice (s.7): Forfeiture threats and device seizures as evidence make the process itself punitive.

Proportionality (s.12): Up-charging lesser conduct via the hate-overlay risks disproportionate penalties in foreseeable cases.

Before a court ever rules, people live under bail terms, lose access to gear, and carry a public accusation. Removing AG consent accelerates that pipeline.

What the Courts Might Say

The Supreme Court has upheld targeted limits on hate speech—but only when laws are narrow and precise. Bill C-9 isn’t. The “look-alike” clause, the “public-interest” gate on defences, and the breadth of protest restrictions are all weak on minimal impairment. Some provisions may survive; others are likely overbroad or vague. Meanwhile, the damage from early charges is already done.

The Context You Can’t Ignore

This bill arrives amid public anger over Gaza, contentious foreign policy, and a rising independent press. In that climate, removing AG consent isn’t an administrative tweak; it’s a power shift. It makes it easier and faster to criminalize edge-case expression and to manage protests through charges, bail, and leverage, rather than debate.

Bottom Line

The problem isn’t the goal of protecting people from hatred. The problem is how Bill C-9 does it.

By removing oversight, criminalizing vague categories of expression, and handing front-line prosecutors wider discretion, C-9 turns dissent into a policing problem long before a judge weighs in. That’s over-reach.

Once that power exists, it won’t be confined to the extremists it claims to target. It will be used where it’s most convenient—against controversial protests and the people who report on them.